Overview of MI for Facilitators

A. Comprehensive Review of MI

There are two major goals when delivering Motivational Interviewing (MI): the first is to develop a strong working alliance, or therapeutic relationship, and the other is to create an atmosphere in which the participant can engage in Change Talk. The former has to do with engaging the participant, and the second is unique to MI and involves the participant verbalizing the benefits to making changes.

Ambivalence is the key to change, and it is a normal and natural part of change. The focus of MI is to manage the ambivalence and acknowledge that the participant has co-existing and conflicting feelings about making the change: “I want to, but I don’t want to.” The goal is for the facilitator to “tap” into the “change” side of the ambivalence by allowing the participant to verbalize the reasons for changing and avoid setting up the situation in which the participant is arguing for the “not change” side of the ambivalence.

This idea comes from the Self-Perception Theory: “The more a person argues on behalf of a position, the more he or she is committed to it.” That is, we believe what we hear ourselves say. Our goal, therefore, is to have the participant “argue” for the reasons to make changes. In addition, when a person publicly takes a position, in this case for engaging in therapy, their commitment to that position increases.

The major thing we want to avoid as facilitators is to set up the dynamic where the participant is arguing for not changing, which occurs when the participant feels like they are being forced or pressured into making a change. This is based on the concept of Reactance, where there is an increase in the rate and attractiveness of a “problem” behavior when a person perceives that his or her personal freedom or decision-making is being infringed upon, challenged, or threatened. It is where the person essentially does the opposite of what they are told to demonstrate free-will and independent decision-making.

The objective of MI, therefore, is to use MI Principles and strategies to allow the participant to say what the facilitator wants to tell them: The benefits of making the change and the costs of staying the same.

When delivering MI, there is always a Target Behavior, something we want the participant to do more/less of, sooner, or more frequently. It is important to identify the target behavior to help the facilitator strategically use MI skills. That is, an MI facilitator does not haphazardly reflect and affirm all the participant’s statements, but rather uses the skills selectively to guide the participant towards the target behavior.

Change Talk is the unique essence of MI and is what is used to move the participant towards the target behavior. There are different “types” of change talk that the facilitator is listening for the participant to verbalize:

- Problem recognition/awareness

- Concern about the problem

- Potential benefits of change

- Costs of not changing

The opposite of change talk is Sustain Talk, that is, the reasons for staying the same and not changing.

B. The MI Spirit: Engaging the Client

B. The MI Spirit: Engaging the Client (PACE)

Partnership:

- Collaboration, Negotiate, Non-authoritarian stance

Acceptance:

- Unconditional positive regard

- Acceptance

- Affirming

Compassion:

- Pursue participant’s best interest

Evocation:

- Draw out the participant’s own desire and reasons for changing

Cultivating Change Talk: OARS

Open-ended Questions: Allows the participant to do the talking and so by doing, allows for Change Talk.

Affirmations: Noting and acknowledging the participant’s actual and specific behaviors and acts that are consistent with the target behavior.

Reflective Listening: This is the major and most important MI tool. The facilitator can reflect feelings, speech, facial expressions, and behavior. In making Reflections, the facilitator makes “presumptions” and verbalizes “hypotheses” of what the participant may be saying; that is, the goal is to reflect the meaning behind the participant’s statement.

There are different “Levels” of reflections:

Simple:

- Repeating – simply repeat what was said

- Rephrasing – slight rephrase/synonyms

Complex (which is the therapist’s goal):

- Paraphrasing – infer meanings/new words

- Reflection of Feeling – emotional dimension

There are other “Styles” of Reflections that the facilitator can use to cultivate change talk, side-step avoidance talk, and manage resistance (discord):

- Amplified, Double-Sided, Metaphor, and Unspoken Emotion.

Summarize: This technique is used to collect then summarize back to the participant the Change Talk statements that have been made. Also, summarizing allows for “linking,” where the facilitator makes “connections” for the participant that they may not be fully aware of. Facilitator: “When you are willing to take a class, you get closer to your goal of getting a job.” Here, the facilitator “links” the participant’s immediate behavior with positive consequences. Finally, summarizing allows for the transitioning to another topic.

NOTE TO FACILITATORS:

Ask-Offer-Ask is a very useful way for the facilitator to impart information, point out inconsistencies on the part of the participant, and provide suggestions or input. It works by first eliciting the participant’s permission to offer information, an observation, or suggestion, then the facilitator provides that information, etc., then the second elicit is to inquire about the participant’s reaction to the observation, or suggestion. This is a respectful and courteous way to impart information to the participant while at the same time maintaining the therapeutic relationship and demonstrating the MI Spirit (e.g., partnership and acceptance).

C. Resistance, Updated

C. Resistance, Updated

In MI, the concept of Resistance has been replaced by two other concepts: Sustain Talk and Discord. The concern about “resistance” is that it is seen as something “inside” or “about” the participant. The facilitator may say: “They are just a resistant participant,” and therefore there is a sense on the part of the facilitator that there is little that can be done because “that is the way the participant is.”

On the other hand, there is something the facilitator can do to address Sustain Talk and Discord. As noted, the concept of Sustain Talk reflects one side of the Ambivalence (the “no change” side) and is represented in this intervention when the participant verbalizes the benefits of not changing and the costs of changing (i.e., avoidance talk). The idea of Discord has to do with the working relationship (i.e., therapeutic alliance), specifically that there is a “rupture” in the relationship and the participant does not feel like there is an alliance or a partnership. The way to address Discord is to focus on the MI Spirit (partnership and acceptance) and using more of the OARS, especially reflective listening.

Ways to handle Sustain Talk

- Simple Reflections: One good general strategy is to respond with non-resistance. A simple acknowledgment of the client’s disagreement, emotion, or perception can permit further exploration rather than defensiveness, thus avoiding the confrontation-denial trap.

“You’re right, you can’t change the past.”

- Double-Sided Reflection: Acknowledge what the client has said and add to it the other side of the client’s ambivalence. This requires the use of information that the client has offered previously, though perhaps not in the same session.

“Your kind of dreading therapy, and yet there’s a part of you who’s excited about making a change.”

“You don’t entirely buy this therapy stuff, and yet there’s some hope that things can improve.”

- Amplified Reflections:

“So, there has never been a time (in your life) that you have successfully faced a difficult situation…?”

(Be sure it is a Reflection and not a closed question.)

If still “none,” facilitate AOA:

A1: “Can I (or other participants) offer some possible situations?”

O: Offer a situation from the military, interpersonal, educational, occupational

A2: “What’s your response?”

- Agreement with a Twist: Offer initial agreement, but then add a slight twist or change of direction. This retains a sense of concurrence between facilitator and participant and allows the facilitator to continue influencing the direction and momentum of change.

“You feel anxious about being around others, and yet when you have associated with others in the past you felt better about yourself.”

“You feel anxious about going out, and yet when you have in the past you had a good time.”

- Asking the participant what they want: Sometimes the participant’s priorities differ from the priorities of others (including the facilitator). A participant will likely be more willing to discuss issues that are important to them. Ambivalence can be reduced, therefore, by having the participant decide on the theme of the interaction. This may require some structure on the part of the facilitator by offering options for the participant to consider, all of which are consistent with the protocol.

- Emphasizing Personal Choice and Control: When people think that their freedom of choice is being threatened, they tend to react by asserting their liberty (e.g., “I’ll show you; nobody tells me what to do”). This is called Reactance. Probably the best antidote for this reaction is to assure the person of what is certainly the truth that in the end, it is the participant who determines what happens. An early assurance of this kind can diminish Reactance.

D. Promoting Change Talk

Promoting Change Talk

As noted, Change Talk is the essence of MI, and the goal in MI is to listen for, elicit, and respond to positive change talk.

Here are some Change Talk examples that the facilitator listens for during a session:

- Problem Recognition/Awareness: Avoidance causes problems.

“I don’t have much to do with my time. I don’t feel productive.”

- Concern about the problem: Avoidance causes distress.

“I feel guilty and ashamed when I don’t have money to help my family.”

- Benefits of Change.

“I will fill better about myself if…”

- Costs of Not doing anything.

“As long as I stay uncommitted…”

Evoking Change Talk

By using the MI basics, OARS and AOA, talk will occur spontaneously as the participant discusses their ambivalence. However, because we want the maximum amount of change talk, there are strategies we can use to evoke it:

- (1) Ask Evocative Questions, (2) Ask for Elaboration & Examples, (3) Look Back, Look Forward.

- (4) Use the Motivation Ruler and (5) Branching.

- Ask Evocative Questions

What are your concerns about keeping the status quo?

If “none,” use an amplified Reflection (not a closed-ended question).

“So, there are (absolutely) no concerns about keeping the status quo…”

“There is (absolutely) no other way you can manage this…”

If still “none,” do AOA:

A1: “Can I offer some possible concerns/options?”

O: Suggest concerns (and/or elicit from teammate) and options

A2: “What’s your response?”

How would taking a class impact your (self-esteem, confidence, social life)?

How would making this change fit with who you are? (Link change with that which they value or prize):

“I’d be a better role model for my kids.”

“It would show that I don’t back down.”

“It would show that I have a strong faith.”

- Ask for Elaboration or Examples

When a Change Talk theme emerges, ask for more detail, examples, or facts:

What time of the day would you go?

What route would you take?

How would you afford it?

For each:

Why one choice over another?

Try to make the elaborations and examples as specific and concrete as possible

- Look Back

“What did you notice when you engaged in positive behaviors in the past?”

If given negatives, ask one to two more times for benefits or positives.

“What else did you notice?”

“What else?”

If nothing, reflect a “negative,” then ask specifically for benefit or positive.

If still nothing, ask teammate

If even still nothing, do AOA.

- Look Forward

If you were to engage in productive behaviors in the future, what would you notice?

If given negatives, repeat from #3 above.

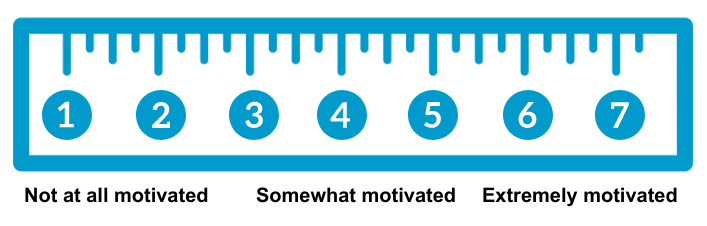

- Use the Motivation Ruler

Ask the participant:

“On a scale from 1 to 10, how motivated are you to change, where 1 is no motivation to change and 10 is extremely motivated to change?”

Motivation Ruler

Follow-up questions:

“Why are you a ___ and not a [next lower number]?”

“What would have to happen for you to move from a to a [next higher number]?”

Do the same thing with “confidence” instead of motivation.

- Branching

Using Branching, the facilitator elaborates the benefits resulting from an initial change that “branches out” to very specific consequences.

E. Responding to Change Talk

E. Responding to Change Talk

EARS is the way the therapist responds to Change Talk:

- Elaboration: Ask the participant for details and examples.

- Affirming: Affirm the participant’s efforts and statements.

- Reflect: Reflect the participants Change Talk.

- Summarize: Gather together and feed back to the participant their Change Talk.

MI review adapted from Miller, W.R., & Rollnick, S. (2023). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change and grow (4th Ed.). New York: The Guilford Press.